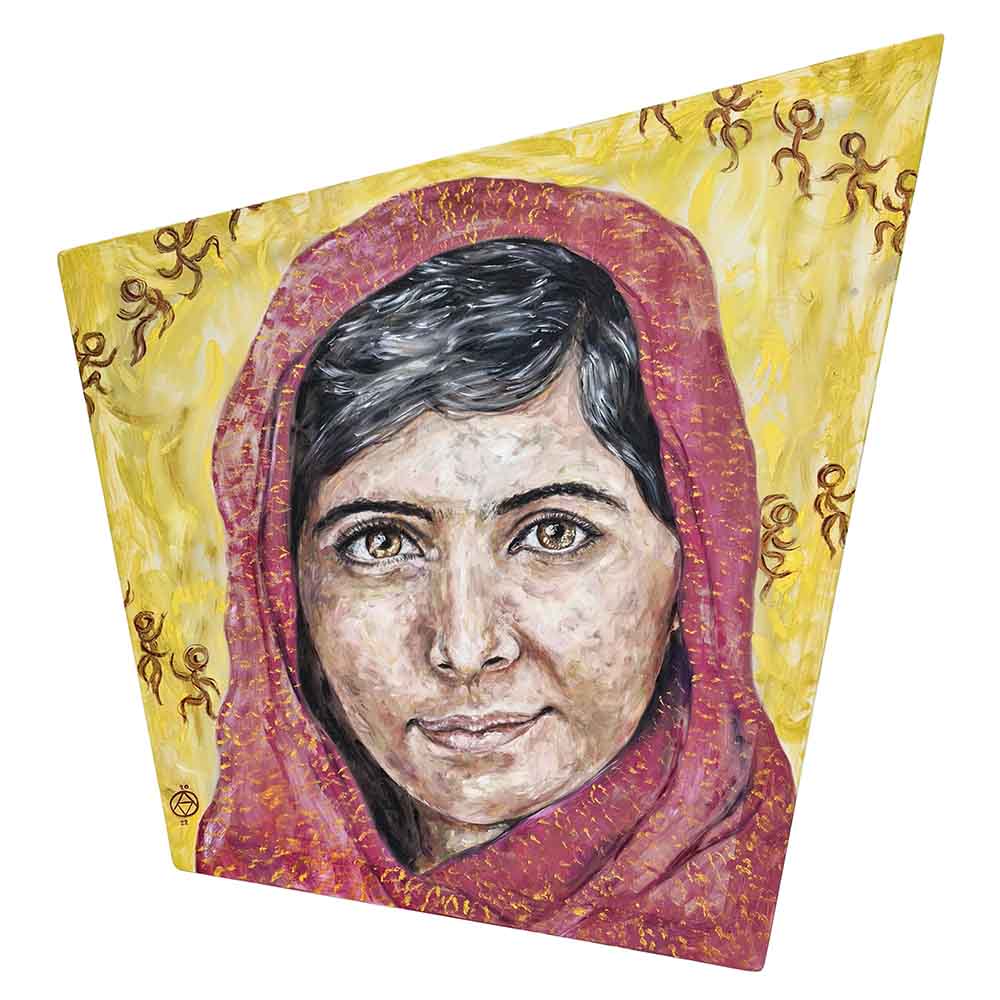

For some people, the idea of ‘taking a bullet’ isn’t simply metaphorical, some thought experiment around willingness and sacrifice.

What made the gunshot wound even more remarkable in the case of this groundbreaking woman is the tender age at which she suffered it and the way she refused to let it define her life or restrict her freedom to fight for her cause.

More than most, Malala Yousafzai is the physical embodiment of defiance, someone unwilling to let even the most terrifying, authoritarian force quell the strength of her message.

It is a breathtakingly simple idea in essence - one that dovetails beautifully with the theme running throughout this collection.

All women have a right to an education.

The Fight For Female Education

As is often the case, what is simple in theory is extremely difficult in practice, virtually impossible in some regimes around the world. Even the more ‘liberalised’ societies of the world are plagued by conscious and unconscious biases that create barriers for women to the same educational and career opportunities as their male counterparts.

But in Pakistan, where she grew up, the barriers were more explicit, the situation starker, as the Pakistani Taliban were challenging the incumbent government and fighting for de facto control of certain regions of the country.

Yousafzai was born in 1997 into a lower middle class family of Sunni Muslims from the northwest of Pakistan. She was home schooled by her father, a poet and activist who operated a chain of private schools; he fed her desire to learn and discuss politics, encouraging her to aim for a career in politics. Even at the age of eleven she was already travelling to press events and calling for a universal right to education in the face of Taliban oppression.

Later that year, in 2008, she began working as a political blogger for BBC Urdu, having been proposed by her father when they asked him for children who could write about their experiences and he couldn’t find any whose families were willing to face the risks. She began to write about her experiences in her local district, Swat, as the Taliban swept through challenging the government’s military. They banned the arts and education, destroyed schools in the name of the decree banning female education, and displayed the severed heads of non-compliant police officers in the streets to serve as a threat to others. At this stage her bravery, mirroring that of her father, was breathtaking. But even as danger was closing in she was undeterred from documenting it.

In February 2009 schooling was permitted again for girls but on the condition that they wear burqas and Yousafzai blogged about her school experiences even as violence continued to rage between the military and the Taliban.

Her father received a death threat after making public criticisms of Taliban fighters around the time she was working with the New York Times on a documentary about the political tensions in the region. The threat served only to highlight the oppression she was fighting against and as she continued to deliver her message to a bigger audience, her platform and reputation grew alongside.

In 2011 she was put forward as a candidate for the KidsRights Foundation’s International Children’s Peace Prize, by no less impressive an admirer than the South African human rights legend Desmond Tutu. Later that year she secured an even higher honour, Pakistan's first National Youth Peace Prize and her work was highlighted by the Prime Minister at the time, awarding her the National Peace Award for Youth.

Assassination Attempt

By the time she was fifteen she was already working on founding the Malala Education Foundation, aimed at enabling poorer girls to attend school. This was the year in which the attempt on her life took place.

The Taliban had decided via an official, unanimous vote among leaders that this fifteen-year girl needed to be assassinated. She posed too much of a threat to their values. And so, on 9 October 2012, a masked gunman intercepted her school bus on its way from an exam hall and demanded to know which of the girls on it was Malala Yousafzai. She revealed herself and was shot in the head, left for dead.

She was taken by military helicopter to a hospital in Peshawar, where doctors worked for several hours to remove the bullet and reduce the swelling; the bullet passed through her head and ended up in her shoulder. Even forty-eight hours later, after the successful procedure, she was given only a 70% chance of survival.

The UK, among many countries who offered to provide the further expert treatment she needed, took care of her from mid October until January 2013 when she was finally discharged. During her recovery she was overwhelmed with love from strangers whose hearts she’d touched.

Where does a life changing moment like this lead and how does one feel after going through this? “My weakness, my hopelessness and my fear had died that day. And I became stronger than before.” says Malala in her interviews, emphasising feeling empowered rather than crushed.

Nobel Peace Prize

One day Malala was sitting in her chemistry class, learning about atoms and whatever else kids learn in school, when her teacher came in bearing exciting news of her Nobel Peace Prize win. Malala, staying true to herself and her purpose, first finished school classes for the day and only then went to give press interviews - after all, education is the very thing she was fighting for.

When she was 18 she founded an all-girls school for Syrian Refugees. The Right to Education Bill passed in Pakistan, largely down to her activist work, with a ten million dollar special fund for education as a result. She is the youngest UN messenger for peace and the youngest Nobel Peace Prize winner; she was the recipient of the third-highest civilian bravery award in Pakistan (Sitara-e-Shujaat) and NASA have even named an asteroid after her.

She is the living embodiment of the belief that one voice, one person can actually make a change.